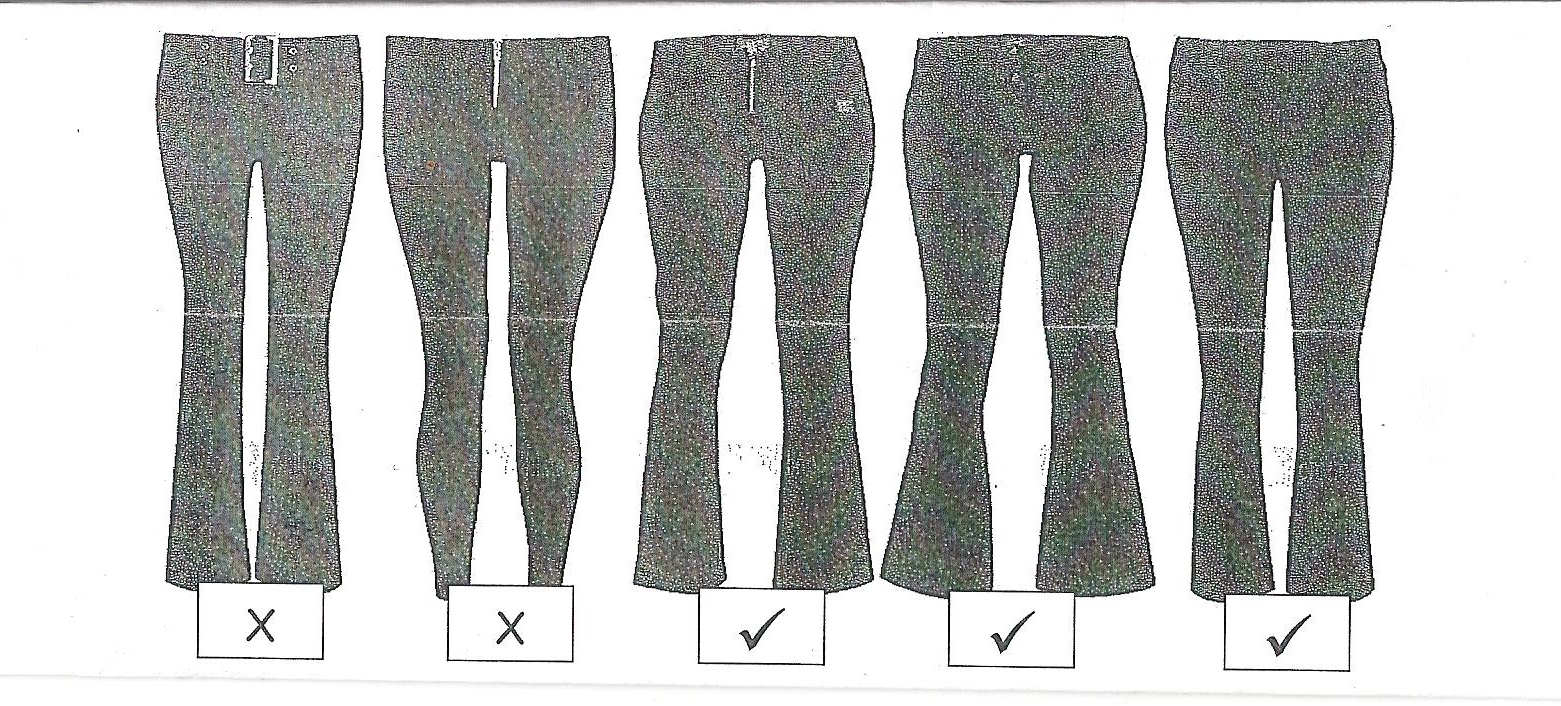

A Bristol secondary school recently sent a letter to parents of female students regarding school uniform. The letter explains that in the last few months “an increasing number of parents” have been purchasing “tight fitting leggings/trousers or jeans” for their daughters. It then asks for the support of parents in purchasing “what the school considers to be appropriate trousers” and included an illustration (see below), indicating which trouser profiles were right and which wrong . Evidently, at least two out of five trouser profiles are now deemed to be the wrong trousers.

A Bristol secondary school recently sent a letter to parents of female students regarding school uniform. The letter explains that in the last few months “an increasing number of parents” have been purchasing “tight fitting leggings/trousers or jeans” for their daughters. It then asks for the support of parents in purchasing “what the school considers to be appropriate trousers” and included an illustration (see below), indicating which trouser profiles were right and which wrong . Evidently, at least two out of five trouser profiles are now deemed to be the wrong trousers.

The school in question has a uniform for both boys and girls (black trousers and white sweatshirt tops), and it is no surprise that teenage pupils are continually trying to subvert the uniform rules and express their individuality with a bit of trendy difference. I remember aged fourteen tying my school tie into the thinnest or fattest of knots depending on what was cool and getting the odd reprimand for not adhering to expected standards of smartness. Whatever you ask to teenagers to wear, they will do their best to subvert it; when you are young, full of creative energy and want to either fit in or assert your independence, that is what you do.

But perhaps there is more to the letter than concerns about girls pushing the boundaries on school uniforms. The giveaway may be that the letter gives no reason why “tight fitting” clothes for teenage girls might be inappropriate. I cannot think that the school would be so coy if the reason was Health & Safety. So it is likely to be the “s” word – and not just “sex”, but more specifically the growing panic among adults about the so-called “sexualisation” of teenage girls. But you have to wonder how such letters and their injunctions help teenage girls or their parents when they don’t explain a school’s concerns about girls dressing in ways considered inappropriately sexual. Surely the education of teenagers should be about inculcating good ethics and enabling right choices. But instead we have a letter to parents that relies on inference. This hardly seems to be in line with the Government’s aim to “create an honest and open culture around sex and relationships” as recently outlined by the Department of Health. Yet given that the latest changes to the UK school science curriculum are to omit any reference to genitalia, puberty or sexual health, perhaps we should not be surprised. Rather than offer parents and their children the chance to question a school uniform decision that touches on adult anxieties about teenage sexuality, this school fails to offer an explanation that might open a debate. Perhaps the same thought process is behind current Government thinking about the place of sex and relationship education in the curriculum.

But a debate about so-called sexualisation is pressing. Not because it is a national problem, but because it isn’t. As Danielle Egan points out in her new book, Becoming Sexual: A Critical Appraisal of the Sexualisation of Girls, we are witnessing another spin of the age-old whirligig of adult anxiety about the sexual corruption of children, particularly teenage girls. This time round girls are at risk from culture (sexualized media and loose sexual morals), people (paedophiles and celebrities) and products (thongs, magazines and, in Bristol, tight fitting leggings and trousers). Allow a young woman to wear inappropriate leg wear to school, and the next stop is promiscuity and pole dancing. Thanks to the school’s fashion vigilance, Bristol’s young women may now have a better chance of avoiding these risks.

Yet all the evidence indicates that young people of both sexes are in less danger of being corrupted by their trousers, or any other part of their clothing, than ever before. Teenage pregnancies are down and falling1, girls aged between 16-19 are the most likely group to use a condom during first sex2, and of the approximately 40% of 16 year old girls engaging in some sort of sexual activity, 60% were doing it with someone with whom they are in a relationship3. Frankly, their sexual behaviour looks a lot more responsible than that of mature men and women in their 40s and 50s, who now have rapidly increasing rates of sexually transmitted infections. The relative maturity of teenage girls was demonstrated in an interview this week on Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour. Two young women, aged 15 and 16, talked eloquently about their online promotion of feminism and equality though TwitterYouthFeministArmy (www.facebook.com/TwitterYouthFeministArmy). Rather than innocents at risk of corrupting sexualisation, these two young women were ready to engage critically with the complex influences that affect their sexual maturation and make personal and political choices about where they stand. As Danielle Egan’s book makes clear, when you start talking to young people about the sexual culture they live in, you get a different picture from what is often imagined by adults.

So if schools want to help young people make mature decisions about the complex issues of fashion, sex and self-expression, their resources might be better spent organising a school debate about the issue. If you are going to set a rule about school uniform based on adult concerns about sexualisation, you might as well ask the kids if they think those fears are justified. That at least might have some educational impact. But sending out letters that impose school uniform rules based on adult anxieties not borne out by evidence is only going to get one teenage response – Whatever! In this instance, it would be justified.

- FPA (2010)

- Mercer, C H et al. (2008). “Who has sex with whom? Characteristics of heterosexual partnerships in a national probability survey and implications for STI risk”, International Journal of Epidemiology 38.1, 1-9.

- Hatherall, B et al. (2005). The Choreography of Condom Use, University of Southampton, Centre for Sexual Health Research.